Government

warnings have hardly restrained one of the world’s most active cryptocurrency

markets.

This

article was first published in the Global Association of Risk Professionals on

April 13, 2018. Co-author: Anisha Sircar

One in every 10

bitcoin transactions in the world takes place in India, according to cryptocurrency

payment company Pundi X. https://pundix.com/

Indian trading in bitcoin grew substantially in 2017, with over 2,500 people

trading daily.

Demonetization of high-denomination Indian currency in November 2016 triggered an explosion of interest in alternative currencies. According to some estimates, the volume of rupee-denominated bitcoin trades is third in the world, behind only U.S. dollars and Japanese yen.

Demonetization of high-denomination Indian currency in November 2016 triggered an explosion of interest in alternative currencies. According to some estimates, the volume of rupee-denominated bitcoin trades is third in the world, behind only U.S. dollars and Japanese yen.

However, on February

1, Finance Minister Arun Jaitley announced – after similar warning statements by

the central bank in 2013 and twice in 2017 – that the state does not consider

cryptocurrencies legal tender. The already-slumping value of bitcoin plummeted

further, by an estimated 6.5%.

Still,

cryptocurrency operators remain positive about the future of virtual currency,

and some economists are convinced that this evolving technology will determine

the future of the global economy.

Not

Explicitly Illegal

The Reserve Bank of

India has taken a stance against licensing any entity to operate with bitcoin

and other virtual currencies, and frequently communicates warnings to users,

holders, and traders about the risks that they are exposing themselves to.

On December 29, 2017,

the Ministry of Finance issued a statement http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=174985 emphasizing that virtual currencies

had no legal tender in India, equating them to Ponzi schemes, and saying that transactions,

because they are encrypted, are “likely being used to carry out

illegal/subversive activities, such as terror-funding, smuggling, drug

trafficking and other money-laundering acts.”

By not declaring virtual

currencies legal, and by choosing not to regulate them without actually declaring

them illegal, the government placed bitcoin in a troublingly grey area. (This

is in contrast to Japan, Canada, Australia, Estonia and Chile, which have

legalized it; and Bolivia, Iceland, Vietnam, Venezuela and others that have

either banned it or imposed punitive measures.)

Moreover, at the

beginning of 2018, Indian cryptocurrency exchanges and payment gateways

received notifications from banks to make immediate changes to the way money

flowed into their platforms, and warning them of account closure if they didn’t

comply.

Koinex,

India’s largest cryptocurrency exchange, posted a statement https://medium.com/koinex-crunch/inr-withdrawals-update-january-7-2018-6279bbe42bd2

on January 7: “A tussle between our payment service partner and their

bank has caused an indefinite delay in the settlement of a large portion of

deposits to Koinex in the past 2 weeks . .

While we have taken firm action, we are also in constant touch with the payment service provider and are providing our complete cooperation to help resolve the matter at the earliest.”

While we have taken firm action, we are also in constant touch with the payment service provider and are providing our complete cooperation to help resolve the matter at the earliest.”

Vague

Authority

The rationale behind

Indian banks’ moves to suspend virtual currencies in India remains unclear, but

hint at a directive from the central bank, which, as noted earlier, has shared

an uneasy relationship with the traction of bitcoin in India.

This directive would fall in line with the general pattern of task forces, nationwide surveys, and notices to traders and financial intermediaries to rein in what governments and banks believe to be a dangerous emerging phenomenon.

This directive would fall in line with the general pattern of task forces, nationwide surveys, and notices to traders and financial intermediaries to rein in what governments and banks believe to be a dangerous emerging phenomenon.

However, despite

statements and actions discouraging people from trading and investing in

bitcoin, several Indian investors began doubling down on the cryptocurrency

market, driving bitcoin prices in the country even higher than global market

trends.

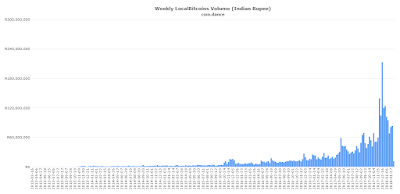

The number of

registrations across exchanges in India surged; bitcoin prices jumped nearly 14-fold

in 2017, hitting an all-time high of $19,500 by mid-December (before plummeting

to $12,000 and then recovering to $17,000 early in 2018). Trading volumes began

doubling in the first weeks of 2018 (see figure 1).

Figure

1

Source: Coin Dance

This general rise in

Indian bitcoin trading volume occurred despite the backdrop of a tumultuous global

cryptocurrency market. Its popularity in India, particularly among celebrities

and entertainers, is due to its appeal primarily as a financial asset,

according to Zebpay, India’s first bitcoin exchange, as well as a market for

remittances.

The drop in bitcoin

trading volumes, from INR 83,214,245 to INR 11,637,525 between January 27 and

February 10, seems to owe itself to the budget announcement. on February 1, in

which Finance Minister Jaitley stated, “The Government does not consider

cryptocurrencies legal tender or coin, and will take all measures to eliminate

use of these crypto assets in financing illegitimate activities or as part of

the payment system.”

Citi India, the only

multinational bank among primary card issuers in India, on February 14 banned

its customers from using the bank’s cards in purchasing cryptocurrencies:

“Given concerns, both globally and locally including from the Reserve Bank of India, cautioning members of the public regarding the potential economic, financial, operational, legal, customer protection and security related risks associated in dealing with bitcoins, cryptocurrencies and virtual currencies, Citi India has decided to not permit usage of its credit and debit cards towards purchase or trading of such bitcoins, cryptocurrencies and virtual currencies.”

“Given concerns, both globally and locally including from the Reserve Bank of India, cautioning members of the public regarding the potential economic, financial, operational, legal, customer protection and security related risks associated in dealing with bitcoins, cryptocurrencies and virtual currencies, Citi India has decided to not permit usage of its credit and debit cards towards purchase or trading of such bitcoins, cryptocurrencies and virtual currencies.”

At the same time, it

was reported https://news.bitcoin.com/more-crypto-jobs-in-india-despite-delhis-stance-on-bitcoin/

that jobs and applicants for employment in the country’s cryptocurrency

sector have increased.

Allure Despite Volatility

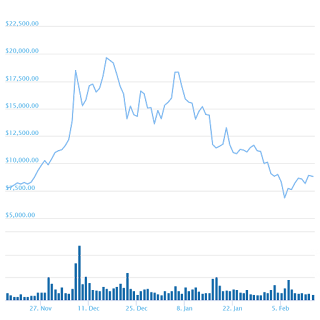

During one period in 2013, bitcoin’s

price increased 85-fold; the following year, it crashed. By the end of 2017,

the big U.S. bitcoin exchange Coinbase said that it had signed 12 million

customers, surpassing the accounts of several established financial

institutions and brokerages, and became the most downloaded iPhone app. https://www.recode.net/2017/12/7/16749536/coinbase-bitcoin-most-downloaded-app-iphone In early February, talk of government and

bank bans caused bitcoin market capitalization to fall 14% in a week. http://fortune.com/2018/02/05/bitcoin-price-crash/ as major

international banks stated their plans or actions of banning customers from

using their cards to purchase it.

A bitcoin user should

invariably tread carefully given the wild price swings.

Source: CoinGecko

Nonetheless, strong

interest stoked by geopolitical unease and distrust in traditional financial

institutions will perhaps continue to add to the allure of a decentralized,

volatile currency outside the control of banks and governments. This has been

happening in India amidst flailing international prices, representing an increasing

demand in India that supply, particularly with institutional forces working

against it, may not be able to handle.

With platforms such

as WhatsApp and Telegram making it even easier to connect sellers and buyers of

virtual currencies (through the means of the platforms themselves, or through

cryptocurrency wallets), the government could be at a loss for ways to stop the

spread of cryptocurrency – because if they prohibit exchanges on platforms, the

transactions will find a way to migrate elsewhere.

Perhaps the overarching

lack of clarity from India’s leadership regarding the legality and mechanics of

virtual currencies in India remains a determinant of their survival in the

country.

The larger question for the global economy, however, perhaps extends beyond the regulation of bitcoin – and seems to stem from that of decentralized technology itself, with its power to replace financial transactions, systems of power and meaning, and the very nature of our tomorrow.

The larger question for the global economy, however, perhaps extends beyond the regulation of bitcoin – and seems to stem from that of decentralized technology itself, with its power to replace financial transactions, systems of power and meaning, and the very nature of our tomorrow.