This article was first published by ISBInsight on December 14, 2018;

Co-authors: Nupur Pavan Bang, Kavil Ramachandran, Anierudh Vishwanathan and

Raveendra Chittoor

http://isbinsight.isb.edu/standalone-family-firms-lead-the-path-to-gender-parity/

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau declared at the 2018 World Economic Forum at Davos, that “time’s up” for gender inequality1. His remark has bearings for the global community.

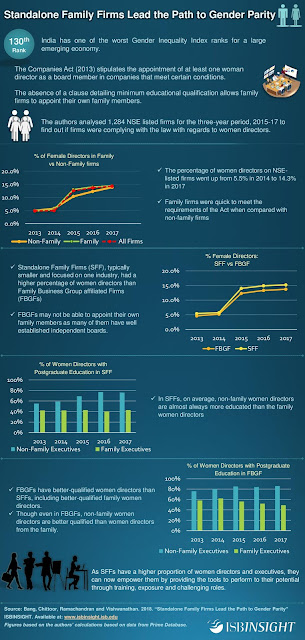

At 130 out of 160 countries, India has one of the worst Gender Inequality Index ranks for a large emerging economy, according to the United Nations Development Programme report2. It needs to take gender very seriously to realise the full potential of the country.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau declared at the 2018 World Economic Forum at Davos, that “time’s up” for gender inequality1. His remark has bearings for the global community.

At 130 out of 160 countries, India has one of the worst Gender Inequality Index ranks for a large emerging economy, according to the United Nations Development Programme report2. It needs to take gender very seriously to realise the full potential of the country.

Now Indian women are making their mark in business (Kiran Mazumdar Shaw,

Nisaba Godrej), politics (Nirmala Sitharaman, Sushma Swaraj), sports (P V

Sindhu, Dipika Pallikal), as well as in science (Tessy Thomas, Priyamvada

Natarajan) like never before. Yet, gender inequality is the hard fact with

women faring poorly in all walks of life, from healthcare to education to

economic participation.

Apart from changing mindsets to welcome the involvement of women in

businesses, the enforcement of the Companies Act (2013) has ensured greater

gender diversity in the boards of listed firms in India.

As the immediate impact of this regulation, requiring every listed company to appoint at least one woman director to their board, the percentage of women directors on National Stock Exchange (NSE)- listed firms went up from 5.5% in 2014 to 12.6% in 2015 and 14.3% in 2017 (Table 1).

As the immediate impact of this regulation, requiring every listed company to appoint at least one woman director to their board, the percentage of women directors on National Stock Exchange (NSE)- listed firms went up from 5.5% in 2014 to 12.6% in 2015 and 14.3% in 2017 (Table 1).

Table 1:

Percentage of Female Directors – All firms

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016

|

2017

|

|

% Women

directors

|

4.9%

|

5.5%

|

12.6%

|

13.7%

|

14.3%

|

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from Prime

Database

Diversity is often seen as a way to infuse novelty into the strategic

decisions taken by the board. Research has found that gender diverse firms are

more sensitive to their stock performance, thereby resulting in better

shareholder value. They have more intense discussions and better monitoring and

oversight3.

Women

Directors in India

Governance in family firms is considered to be a black box by many analysts

and investors. The independent directors’ role is thought to be more ceremonial

in nature. Yet, the quality of the Board of Directors is an important

characteristic of a well-governed firm.

Given this perception, we analysed 1,284 NSE listed firms for the

three-year period, 2013 to 2017 to find out the specifics of women directors

being appointed by family firms. We found that contrary to the general belief,

the family firms were quick to meet the requirements of the Act (Table 2).

Heterogeneity within family firms was captured through the analysis of

Standalone Family Firms (SFFs) separately from that of the Family Business

Group affiliated Firms (FBGFs). FBGFs are firms that are parts of a group of

firms owned and controlled by a family4.

For example, Reliance Industries Ltd. and Network 18 are both part of the Mukesh Ambani-led Reliance group. On the other hand, SFFs are typically smaller firms, focused on one industry and the only listed company owned and controlled by the family.

For example, Reliance Industries Ltd. and Network 18 are both part of the Mukesh Ambani-led Reliance group. On the other hand, SFFs are typically smaller firms, focused on one industry and the only listed company owned and controlled by the family.

Table 2:

Percentage of Women Directors in Family and Non-Family Firms

Ownership

|

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016

|

2017

|

Non-Family

|

5.0%

|

5.8%

|

10.4%

|

12.3%

|

13.9%

|

Family

|

4.9%

|

5.4%

|

13.0%

|

14.0%

|

14.4%

|

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from Prime

Database

The study revealed that on an average (Table 2), family firms had a

higher percentage of women directors on their boards. Further, we found that

the SFFs had a higher percentage of women directors when compared to the FBGFs

(Table 3).

Table

3: Percentage of Female Directors in

Family Firms

Ownership

|

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016

|

2017

|

FBGF

|

4.6%

|

5.2%

|

12.3%

|

13.3%

|

13.7%

|

SFF

|

5.4%

|

5.7%

|

14.0%

|

14.9%

|

15.2%

|

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from Prime

Database

The absence of a clause detailing minimum educational qualifications and

professional experience makes it easy for the promoters of smaller firms (that

are typically SFFs), to comply with the Act by appointing their own female

family members as directors without foregoing their administrative power5.

FBGFs may not be able to appoint their own family members very easily as many

of them have well established independent boards.

As can be seen from Table 4, non-family women directors are almost

always more educated than the family women directors. In general, FBGFs have

better-qualified women directors than SFFs, including better-qualified family

women directors. There is clearly a need to specify the minimum level of

qualification in the Act.

Table 4: Women Directors with Postgraduate

Education in Family Firms

SFF

|

FBGF

|

|||

Non-Family Women

Directors

|

Family Women Directors

|

Non-Family Women

Directors

|

Family Women Directors

|

|

2013

|

55%

|

42%

|

76%

|

58%

|

2014

|

59%

|

42%

|

80%

|

62%

|

2015

|

69%

|

43%

|

85%

|

56%

|

2016

|

77%

|

40%

|

84%

|

52%

|

2017

|

76%

|

42%

|

86%

|

49%

|

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from Prime

Database

Executive

directors:

Executive

directors:

While the proportion of executive directors, both male and female, in

family firms was lower than in non-family firms, the former had a higher

proportion of women executive directors.

Among family firms, SFFs had higher proportions of executive directors and higher proportions of women executive directors than the FBGFs. Women executives from the family again accounted for much of this difference.

Among family firms, SFFs had higher proportions of executive directors and higher proportions of women executive directors than the FBGFs. Women executives from the family again accounted for much of this difference.

SFFs have higher numbers of women executives from the family as the

firms are smaller and have fewer employees and professionals.

These women’s proximity to company operations gives them more chance to observe and influence the process of strategy implementation. When the opportunity arises, they are, thus, more likely to be in substantial roles such as the executive director.

These women’s proximity to company operations gives them more chance to observe and influence the process of strategy implementation. When the opportunity arises, they are, thus, more likely to be in substantial roles such as the executive director.

Independent

directors:

To promote a meaningful debate, bring in diversity in views and ensure

value creation for all stakeholders, family business researchers have argued

that it is important to have truly independent directors on corporate boards6.

Family firms had significantly higher proportions of independent directors

than non-family firms but they had a lower proportion of independent women

directors as the proportion of directors from the family is higher.

Concluding

Thoughts

Increasing gender diversity will require sincere commitment and cautious

implementation plans from companies. SFFs are already doing well in terms of

the proportion of women directors and women executive directors. We would argue

that SFFs can now lead in actually empowering these women directors by

providing them with the tools to perform to their potential through training,

exposure and clear and challenging roles.

Not least, they need to put in place appropriate gender agnostic performance management systems. While interventions at various levels to promote gender parity provide an impetus, their implementation in spirit is in the hands of the firms and individuals.

Not least, they need to put in place appropriate gender agnostic performance management systems. While interventions at various levels to promote gender parity provide an impetus, their implementation in spirit is in the hands of the firms and individuals.

Know

More

1 See Justin Trudeau’s remarks

at the 2018 World Economic Forum, accessed 17 October 2018:

https://www.weforum.org/press/2018/01/justin-trudeau-delivers-full-throated-feminist-address-announces-new-tpp-deal/

2 Accessed 17 October 2018:

http://hdr.undp.org/en/composite/GII

3 For more on this literature,

see among others Adams and Ferreira (2009); Terjesen, Sealy and Singh(2009);

Srinidhi, Gul and Tsui (2011). Adams,

R.B. and Ferreira, D., 2009. Women in the boardroom and their impact on

governance and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 94(2), pp.291-309.

Srinidhi, B., Gul, F. A. and Tsui, J., 2011. Female

directors and earnings quality. Contemporary Accounting Research, 28(5),pp.

1610-1644

Terjesen, S., Sealy, R. and Singh, V., 2009. Women

directors on corporate boards: A review and research agenda. Corporate

Governance: An International Review, 17(3), pp. 320–337

4 For more, see Bang, Ray and

Ramachandran (2017): Bang, N.P., Ray, S. and Ramachandran, K., 2017. Family

business – The emerging landscape: 1990-2015. Thomas Schmidheiny Centre for

Family Enterprise, Indian School of Business: Hyderabad, India

5 Faccio, Lang and Young (2001)

also describe this effect: Faccio, M., Lang, L.H and Young, L., 2001. Debt and

corporate governance. In Meetings of Association of Financial Economics, New

Orleans

6 For example, see studies by

Fama (1980), Fama and Jensen (1983); Miller and Le Breton-Miller (2006).

Fama, E.F., 1980. Agency problems and theory of the

Firm. Journal of Political Economy, 88(2), pp. 288-307

Fama, E.F. and Jensen, M.C., 1983. Separation of ownership

and control. The Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), pp. 301-325

Miller, D. and Le Breton-Miller, I., 2006. Family

governance and firm performance: Agency, stewardship and capabilities. Family

Business Review, 19, pp. 73-87